Medical billing, a payment process in the United States healthcare system, is the process of reviewing a patient’s medical records and using information about their diagnoses and procedures to determine which services are billable and to whom they are billed.[1]

This bill is called a claim.[2] Because the U.S. has a mix of government-sponsored and private healthcare, health insurance companies – otherwise known as payors – are the primary entity to which claims are billed for physician reimbursement.[3] The process begins when a physician documents a patient’s visit, including the diagnoses, treatments, and prescribed medications or recommended procedures.[4] This information is translated into standardized codes through medical coding, using the appropriate coding systems such as ICD-10-CM and Current Procedural Terminology (CPT). A medical biller then takes the coded information, combined with the patient’s insurance details, and forms a claim that is submitted to the payors.[2]

Payors evaluate claims by verifying the patient’s insurance details, medical necessity of the recommended medical management plan, and adherence to insurance policy guidelines.[4] The payor returns the claim back to the medical biller and the biller evaluates how much of the bill the patient owes, after insurance is taken out. If the claim is approved, the payor processes payment, either reimbursing the physician directly or the patient.[5] Claims that are denied or underpaid may require follow-up, appeals, or adjustments by the medical billing department.[5]

Accurate medical billing demands proficiency in coding and billing standards, a thorough understanding of insurance policies, and attention to detail to ensure timely and accurate reimbursement. While certification is not legally required to become a medical biller, professional credentials such as the Certified Medical Reimbursement Specialist (CMRS), Registered Health Information Administrator (RHIA), or Certified Professional Biller (CPB) can enhance employment prospects.[6] Training programs, ranging from certificates to associate degrees, are offered at many community colleges, and advanced roles may require cross-training in medical coding, auditing, or healthcare information management.

Medical billing practices vary across states and healthcare settings, influenced by federal regulations, state laws, and payor-specific requirements. Despite these variations, the fundamental goal remains consistent: to streamline the financial transactions between physicians and payors, ensuring access to care and financial sustainability for physicians.

History

In 18th century England, physicians were not legally permitted to charge fees for their services or take legal action to collect payments. Instead, patients would offer “honoraria,” which were voluntary payments inspired by what was believed to be a Roman custom.[7] This honorarium rule applied only to non-surgeon physicians.[8] Meanwhile, surgery was treated as a “public calling,” allowing courts to cap surgeons’ fees to reasonable amounts. The honorarium rule for non-surgeon physicians and the public calling status for surgeons highlighted the unique, non-commercial constraints on medical professionals at the time.[7][8] These constraints further emphasized professionalism over commerce, distinguishing these professions from regular businesses.

In the 19th century, the American colonies abandoned the English honorarium and public calling principles.[9] Instead, physicians could use standard contract and commercial law to set and collect fees.[9] Unlike in England, U.S. courts viewed medical services like goods with fixed prices, allowing physicians to sue for outstanding payments and freely set terms, independent of obligations tied to public service.[7]

Before the spread of health insurance, doctors charged patients according to what they thought each patient could afford. This practice was known as sliding fees and became a legal rule in the 20th century in the U.S.[7][10] Eventually, changing economic conditions and the introduction of health insurance in the mid-20th century ushered an end to the sliding scale.[11] Health insurance became a conduit for billing, and it standardized fees by negotiating fee schedules, eliminating additional charges, and restricting discounts that the sliding scale offered.[7]

For several decades, medical billing was done almost entirely on paper. However, with the advent of medical practice management software, also known as health information systems, it has become possible to efficiently manage large amounts of claims. Many software companies have arisen to provide medical billing software to this particularly lucrative segment of the market. Several companies also offer full portal solutions through their web interfaces, which negates the cost of individually licensed software packages. Due to the rapidly changing requirements by U.S. health insurance companies, several aspects of medical billing and medical office management have created the necessity for specialized training. Medical office personnel may obtain certification through various institutions who may provide a variety of specialized education and in some cases award a certification credential to reflect professional status.

Billing process

Visiting a doctor might feel like a straightforward one-on-one interaction, but it is actually part of a much larger and more complex system involving information exchange and payment processing. While an insured patient typically interacts only with a healthcare provider during a visit, the encounter is part of a three-party system.

The first party in this system is the patient. The second is the healthcare provider, a term that encompasses not only physicians but also hospitals, physical therapists, emergency rooms, outpatient facilities, and other entities delivering medical services. The third and final party is the payor, typically an insurance company, which facilitates reimbursement for the services rendered.

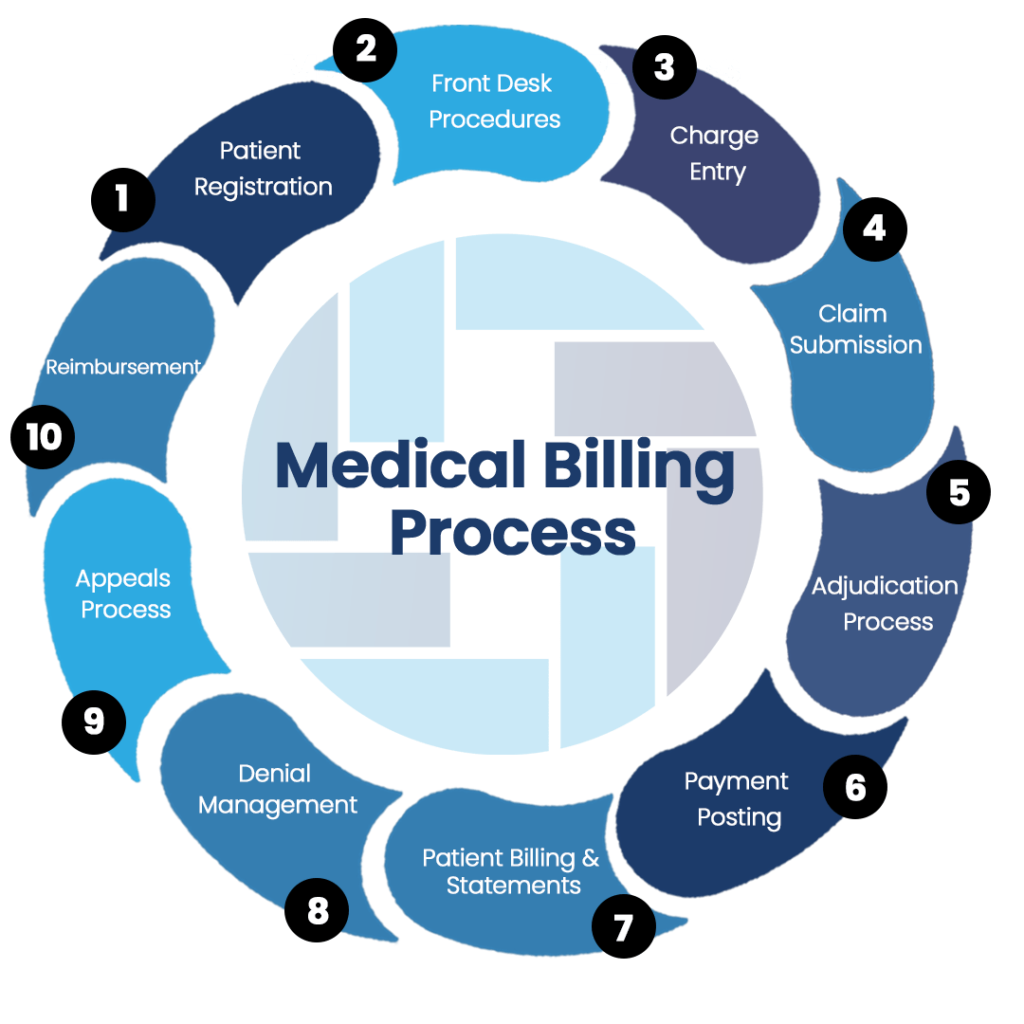

Medical billing involves creating invoices for services rendered to patients, a process known as the billing cycle or Revenue Cycle Management (RCM).[12] RCM encompasses the entire revenue collection process for a healthcare facility, beginning with the design of the RCM workflow. This cycle can take anywhere from a few days to several months, often requiring multiple interactions before achieving resolution.[13] The relationship between healthcare providers and insurance companies resembles that of a vendor and subcontractor: healthcare providers contract with insurers to deliver services to covered patients.

Step 1: Patient Registration[4]

The process begins when a patient schedules an appointment. For new patients, this involves gathering essential information, including their medical history, insurance details, and personal data. For returning patients, the focus is on updating records with the latest reason for the visit and any changes to their personal or insurance information. This foundational step ensures the practice has accurate and up-to-date records for billing and care coordination.

Step 2: Determining Financial Responsibility[4]

Once the patient is registered, the next step is to identify which treatments or services their insurance plan will cover. Insurance policies often include specific guidelines regarding covered procedures and exclusions, and these rules can change annually. To avoid billing complications, it is critical for the healthcare provider to stay informed about the most recent coverage requirements for each insurance plan.

Step 3: Assigning Codes[4]

This is where medical billing departs from medical coding. Medical coders are responsible for this step and they rely on two standardized coding systems to document and classify the services provided, which will eventually be put into a bill by medical billers.

ICD Codes: Developed by the World Health Organization, the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes describe the conditions or symptoms being evaluated or treated. The current version, ICD-10, will transition to ICD-11 in 2025, requiring updated coding practices.[14]

CPT Codes: Created by the American Medical Association (AMA), Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) codes correspond to the procedures or treatments performed by the healthcare provider. These codes are essential for accurately billing and receiving reimbursement.[15]

For every patient encounter, providers must record both ICD codes to identify the diagnosis and CPT codes to document the treatment. Given the vast number of codes—approximately 70,000 for ICD and over 10,000 for CPT—using advanced medical billing software is recommended to streamline the coding process, reduce errors, and ensure compliance with current standards.[16]

These steps set the stage for efficient claims submission and payment, forming the backbone of the billing cycle.

Step 4: Creating the Superbill[4]

Once a patient’s visit is complete and they check out, the next step is to compile all the relevant information into a document called the Superbill. This document serves as the foundation for the reimbursement claim submitted to the payor. The Superbill includes essential details about the provider, the patient, and the visit, ensuring that the claim is complete and accurate for efficient processing.

Components of a Superbill

Provider Information

Full Name

National Provider Identifier (NPI) Number

Practice Location

Contact Information

Referring Provider’s Name and NPI (if applicable)

Provider’s Signature

Patient Information

Full Name

Date of Birth

Contact Information

Insurance Details

Visit Information

Date of Visit

Relevant CPT and ICD Codes

Fees Charged for Services

Duration of Visit

By consolidating this information into the Superbill, healthcare providers create a structured summary that facilitates claim submission and ensures proper documentation for payor review. This step is vital in maintaining accuracy and minimizing errors during the medical billing process.

Step 5: Preparing and Submitting Claims[4]

Using the Superbill, the medical biller creates a detailed claim and submits it to the insurance company for reimbursement. Accuracy and completeness are critical during this step to ensure the claim is accepted on the first submission—referred to as a clean claim. Achieving a high clean claims rate is a key metric for measuring the efficiency of the billing cycle. Creation of the claim is where medical billing most directly overlaps with medical coding because billers take the ICD/CPT codes used by the medical coders and creates the claim.

Step 6: Monitoring payor Adjudication[4]

Once the payor receives the claim, they review it to determine whether it is accepted, denied, or rejected. Understanding these outcomes is essential:

Accepted Claims

Accepted claims are processed for payment.

Payment amounts depend on the specifics of the patient’s insurance plan and may not cover the entire billed amount.

Denied Claims

These claims are properly filed but do not meet the payor’s criteria for payment.

Common reasons include billing for services not covered by the plan, highlighting the importance of verifying insurance coverage during patient registration.

Denied claims require investigation to identify the issue and prevent future occurrences.

Rejected Claims

Rejected claims cannot be processed, typically due to errors or omissions in the filing process.

Unlike denied claims, rejected claims must be corrected and resubmitted.

Failure to address rejected claims can lead to significant revenue loss, making timely rework essential.

Step 7: Creating Patient Statements[4]

After the payor processes the claim and pays their portion, any remaining balance is billed to the patient in a separate statement. Ideally, patients will promptly settle their accounts, completing the billing cycle. However, delays or non-payments are common, requiring providers to follow up to ensure full reimbursement.

Step 8: Following Up on Payments[4]

Following up on outstanding claims and patient statements is a crucial step in capturing revenue that might otherwise be lost. Practices should focus on reducing payment barriers to make the process as simple as possible for patients.

Implementing a patient portal with online payment options can streamline the process, allowing patients to pay their bills at their convenience.

A self-service system encourages on-time payments and reduces the likelihood of accounts being sent to collections.

Consistent follow-ups and clear communication help address common billing issues and improve overall payment rates.

By maintaining an efficient follow-up system, practices can minimize revenue leakage and keep the billing cycle running smoothly.

Visiting a doctor might feel like a straightforward one-on-one interaction, but it is actually part of a much larger and more complex system involving information exchange and payment processing. While an insured patient typically interacts only with a healthcare provider during a visit, the encounter is part of a three-party system.

The first party in this system is the patient. The second is the healthcare provider, a term that encompasses not only physicians but also hospitals, physical therapists, emergency rooms, outpatient facilities, and other entities delivering medical services. The third and final party is the payor, typically an insurance company, which facilitates reimbursement for the services rendered.

Electronic billing

A practice that has interactions with the patient must now, under HIPAA law 1996, send most billing claims for services via electronic means. Prior to actually performing service and billing a patient, the care provider may use software to check the eligibility of the patient for the intended services with the patient’s insurance company. This process uses the same standards and technologies as an electronic claims transmission with small changes to the transmission format, this format is known specifically as X12-270 Health Care Eligibility & Benefit Inquiry transaction.[17] A response to an eligibility request is returned by the payor through a direct electronic connection, or more commonly their website. This is called an X12-271 “Health Care Eligibility & Benefit Response” transaction. Most practice management/EM software will automate this transmission, hiding the process from the user.[18]

This first transaction for a claim for services is known technically as X12-837 or ANSI-837. This contains a large amount of data regarding the provider interaction, as well as reference information about the practice and the patient. Following that submission, the payor will respond with an X12-997, simply acknowledging that the claim’s submission was received and that it was accepted for further processing. When the claim(s) are actually adjudicated by the payor, the payor will ultimately respond with a X12-835 transaction, which shows the line-items of the claim that will be paid or denied; if paid, the amount; and if denied, the reason.

Payment

In order to be clear on the payment of a medical billing claim, the health care provider or medical biller must have complete knowledge of different insurance plans that insurance companies are offering, and the laws and regulations that preside over them. Large insurance companies can have up to 15 different plans contracted with one provider. When providers agree to accept an insurance company’s plan, the contractual agreement includes many details, including fee schedules which dictate what the insurance company will pay the provider for covered procedures, and other rules such as timely filing guidelines.

Providers typically charge more for services than what has been negotiated by the physician and the insurance company, so the expected payment from the insurance company for services is reduced. The amount that is paid by the insurance is known as an “allowed amount”.[19] For example, although a psychiatrist may charge $80.00 for a medication management session, the insurance may only allow $50.00, and so a $30.00 reduction (known as a “provider write off” or “contractual adjustment”) would be assessed. After payment has been made, a provider will typically receive an Explanation of Benefits (EOB) or Electronic Remittance Advice (ERA) along with the payment from the insurance company that outlines these transactions.

The insurance payment is further reduced if the patient has a copay, deductible, or a coinsurance. If the patient in the previous example had a $5.00 copay, the physician would be paid $45.00 by the insurance company. The physician is then responsible for collecting the out-of-pocket expense from the patient. If the patient had a $500.00 deductible, the contracted amount of $50.00 would not be paid by the insurance company. Instead, this amount would be the patient’s responsibility to pay, and subsequent charges would also be the patient’s responsibility, until his or her expenses totaled $500.00. At that point, the deductible is met, and the insurance would issue payment for future services.

A coinsurance is a percentage of the allowed amount that the patient must pay. It is most often applied to surgical and/or diagnostic procedures. Using the above example, a coinsurance of 20% would have the patient owing $10.00 and the insurance company owing $40.00.

Steps have been taken in recent years to make the billing process clearer for patients. The Healthcare Financial Management Association (HFMA) unveiled a “Patient-Friendly Billing” project to help healthcare providers create more informative and simpler bills for patients.[20] Additionally, as the Consumer-Driven Health movement gains momentum, payors and providers are exploring new ways to integrate patients into the billing process in a clearer, more straightforward manner.

Medical billing services

Some providers outsource their medical billing to a third parties, known as medical billing companies, which provide medical billing services. One goal of these entities is to reduce the amount of paperwork for medical staff and to increase efficiency, providing the practice with the ability to grow. The billing services which can be outsourced include regular invoicing, insurance verification, collections assistance, referral coordination, and reimbursement tracking.[21]

Practices have achieved cost savings through group purchasing organizations (GPO).[22]

Medical billing vs medical coding

While medical billing and medical coding are closely related and often go hand-in-hand, they serve distinct functions in the healthcare industry. Medical coders are responsible for translating healthcare services, diagnoses, and procedures into standardized codes used for billing purposes. These codes ensure that healthcare providers receive accurate reimbursement from insurance companies. On the other hand, medical billing involves using these codes to create and submit claims to insurance companies and patients. In essence, medical coders lay the foundation by providing the necessary codes, while medical billers use those codes to process payments and manage patient accounts. Understanding both roles is crucial, as they work together to ensure the financial stability of healthcare providers.

See also

- Electronic medical record

- Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System

- International Classification of Diseases (ICD codes)

- Medically Unlikely Edit

- National Uniform Billing Committee

References

- ^ “What is Medical Billing?”. www.aapc.com. Retrieved 2024-11-12.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “20 CFR 10.801 — How are medical bills to be submitted?”. www.ecfr.gov. Retrieved 2024-11-21.

- ^ “US Healthcare System Overview-Background”. ISPOR.org. Retrieved 2024-11-21.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e f g h i j Staff, CollaborateMD (2022-08-25). “A Guide to the Medical Billing Process + Infographic”. CollaborateMD. Retrieved 2024-11-21.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “Healthcare reimbursement: how it works for providers”. Sermo. 2023-05-10. Retrieved 2024-11-21.

- ^ “Medical Billing Certification – Certified Professional Biller – CPB Certification”. www.aapc.com. Retrieved 15 April 2019.

- ^ Jump up to:a b c d e Hall, Mark A.; Schneider, Carl E. (August 2008). “Learning from the Legal History of Billing for Medical Fees”. Journal of General Internal Medicine. 23 (8): 1257–1260. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0605-1. ISSN 0884-8734. PMC 2517971. PMID 18414955.

- ^ Jump up to:a b Crawford, C. (2000-01-01). “Patients’ Rights and the Law of Contract in Eighteenth-Century England”. Social History of Medicine. 13 (3): 381–410. doi:10.1093/shm/13.3.381. ISSN 0951-631X. PMID 14535268.

- ^ Jump up to:a b “JOSIAH QUINCY JR., THE LAW REPORTS”. Colonial Society of Massachusetts. Retrieved 2024-11-12.

- ^ Cabot, Hugh (March 1, 1935). The Doctor’s Bill (1st ed.). Columbia University: Columbia University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0231933407.

- ^ “H. M. Somers & A. R. Somers, Doctors, Patients and Health Insurance. The Organization and Financing of Medical Care. Washington, The Brookings Institution, 1961, xix p. 576 p., $ 7.50”. Recherches Économiques de Louvain/ Louvain Economic Review. 28 (8): 792. December 1962. doi:10.1017/S077045180010257X. ISSN 0770-4518.

- ^ “What Is Revenue Cycle Management (RCM)?”. www.aapc.com. Retrieved 2024-11-21.

- ^ “Average Days from Date of Service to Final Payment – RCM Metrics – MD Clarity”. www.mdclarity.com. Retrieved 2024-11-21.

- ^ “ICD-11 Implementation”. www.who.int. Retrieved 2024-11-21.

- ^ “CPT® Codes”. American Medical Association. 2024-11-20. Retrieved 2024-11-21.

- ^ “Overview of Coding & Classification Systems | CMS”. www.cms.gov. Retrieved 2024-11-21.

- ^ “X12 270 CM Glossary”.

- ^ “Medicare Coordination of Benefits (COB) System Interface Specifications 270/271 Health Care Eligibility Benefit Inquiry and Response HIPAA Guidelines for Electronic Transactions” (PDF). the U.S. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Retrieved November 4, 2020.

- ^ “What is an allowed amount?”.

- ^ “Patient Friendly Billing Project”. www.hfma.org. Retrieved 2015-09-07.

- ^ Tom Lowery (2013). “8 Ways Outsourcing Can Help Hospitals and Patients”. HuffPost.

- ^ Reese, Chrissy (30 May 2014). “Realizing Affordable Healthcare: The Advent of Medical Billing”. Fiscal Today. Retrieved 11 June 2014.